Last summer, the poetry editor of a major magazine confessed to me that he was confused about AI. I had just reported for The Atlantic on a corpus of nearly 200,000 pirated books that tech companies were using to train generative AI systems. "My only claim to any kind of real ’training,’" wrote the editor, "is the corpus of poets I’ve read." He admitted, with some embarrassment, that he wasn’t sure how to articulate the meaningful differences between himself and ChatGPT.

A few months later, the cultural critic Louis Menand claimed there were no meaningful differences: "A.I. is only doing what I do when I write a poem…[but] more efficiently," he wrote in The New Yorker. A system like ChatGPT "is reviewing all the poems it has encountered and using them to make something new." Essentially, Menand said, humans and AI use the same process: they look at past work, perform a kind of transformation of that work, and output something new. Thus, AI makes legitimate art despite being an algorithm.

This is a radically new understanding of creativity, which, until recently, required things like experience, imagination, empathy, taste, desire, humor, and an ability to manipulate meanings. Non-sentient logic machines, were considered incapable of making art. But generative AI, with its clever statistical methods, has made the computer seem like a legitimate artist. It’s also made those classic human faculties seem unnecessary or romantic.

But this equivalence between AI and humans requires taking a rather schematic view. It’s true that both have inputs and outputs and some kind of transformational function in between. But are those all the relevant facts?

There happen to be objective, measurable differences between the internal processes of humans and AI. A striking example is the phenomenon of "model collapse." An AI model trained on human prose will generate new prose that looks coherent and plausibly human. But if you train that same model on AI-generated prose, the output devolves into gibberish. The same goes for image generators.

AI’s creations might look fine at a glance, but they’re missing something vital. Something even AI can’t function without. What is it? And what are the consequences of ignoring it?

Some say the problem with AI is that it can’t surprise us. The art critic William Deresiewicz has written that "AI operates by making high-probability choices: the most likely next word, in the case of written texts. Artists…do the opposite. They make low-probability choices." Menand, too, admits that a "big difference" between himself and a large language model (LLM) is that he’s "trying to avoid, wherever possible, the statistically most common" next word.

But generative AI can be programmed to make low-probability choices too. I fired up Llama 2, a large language model made by Meta, and had it complete the same sentence several times, while increasing the "temperature." Temperature is a setting that controls an LLM’s tendency to use lower-probability words. It’s often cited as the way to make them "more creative."

Temperature = 1: The role of consciousness in human culture is still not well understood. Consciousness is the key to human existence. The role of consciousness in human evolution is still not well understood.

Temperature = 5: The role of consciousness in human culture may not seem very evident at a glance; in some ways our civilisation appears to exist in deficiency. But the very fact our minds exist, our

Temperature = 10: The role of consciousness in human culture is still very mysteriously unclear to modern science but it appears very clearly as the most dominant force driving culture throughout its history (and even today in certain cultu...

Temperature = 50: The role of consciousness in human culture is still poorley investiget, even in science-cracy of our times… But, what does it really take us from a mere being into being human…

Temperature = 100: The role of consciousness in human culture may have evolves, but in many cases we still seem unable (perverse? stupid?? ignor?ent) in understanding and using conscious intelligence.

I could keep turning up the temperature, but I think it’s clear where this is headed. These sentences feature unusual choices, but they don’t exactly radiate a sense of intelligence. They don’t even address the question I’m clearly asking. We need creative writing to do more than surprise us.

Let’s consider the intriguing parts of Llama 2’s output: "science-cracy" and "ignor?ent" are weird language-objects. To some people, they might look like the seeds of something experimental. Are they like the odd grammar of Gertrude Stein or the chopped-up sentences of Eimear McBride’s 2014 novel, A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing? Writers experiment with language all the time (though eXpErImEnTs can f4il in rather annoying fashion). What makes some of them succeed?

The task of artists and writers is not simply to make unexpected choices but to make those choices feel natural. Llama’s "ignor?ent" is gibberish rather than art because it lacks a context that could make it meaningful. Excerpts from Eimear McBride’s novel are similarly nonsensical out of context—"Two me. Four you five or so. I falling. Reel table leg to stool. Grub face into her cushions."—but the style makes perfect, tragic sense given the particular psychic damage of the book’s narrator.

Or, think of the oft-quoted lines from The Big Lebowski. Alone, they’re nothing: "That rug really tied the room together." "You are entering a world of pain." "That’s just, like, your opinion, man." These banalities became resonant and memorable because the Coen brothers created Donny, Walter, The Dude, and an off-kilter world for them to bowl and moon around in.

LLMs can’t do this kind of world-building. When they succeed at writing, they do so because what’s being asked of them is deceptively simple. Consider joke-writing. OpenAI has trained an LLM to write Onion-style headlines. "Experts Warn that War in Ukraine Could Become Even More Boring" is one of its best efforts. "Story of Woman Who Rescues Shelter Dog With Severely Matted Fur Will Inspire You to Open a New Tab and Visit Another Website" is another. They’re not brilliant, but they’re passable. At first, it seems surprising that an LLM can do the task this well.

But here’s the problem. A lot of Onion headlines are formulaic. Its writers have perfected a style that mixes highfalutin journalistic formality with the lowly, un-newsworthy trivia of daily life. Even some of my all-time favorites, like "Area Bassist Fellated," are just good variations on the theme. Writing a headline in this style is a bit like playing mad-libs. The built-in joke is that the news is supposed to be important but the minutiae of our lives always matters more.

Some Onion headlines are less formulaic. The wonderful "CIA Realizes It's Been Using Black Highlighters All These Years" is not something you arrive at by plugging clever words into a formula. It’s more complexly referential. You have to know about redacted documents and highlighters. An LLM has no mechanism for understanding such things. It functions on the level of words, not meanings, and it cannot magically start to do otherwise (despite some AI enthusiasts' misleading claims about "black boxes" and "emergent" capabilities).

Similarly, fictional world-building requires a feel for the right combination of the normal and the strange. The possibility-space of interesting worlds (and original jokes) is exponentially larger than the possibility-space of the grammatically correct and coherent paragraphs ChatGPT spews out. Creating something as unique and compelling as The Big Lebowski (let alone Twin Peaks or Eimear McBride’s novel) would require an entirely different type of technology.

But so, who cares? Why not use AI anyway, and revise or expand on its output? One defender of generative AI has called it "just a tool, like the paintbrush," and many creative folks agree. They use generative AI to make early drafts and concepts that they revise and refine.

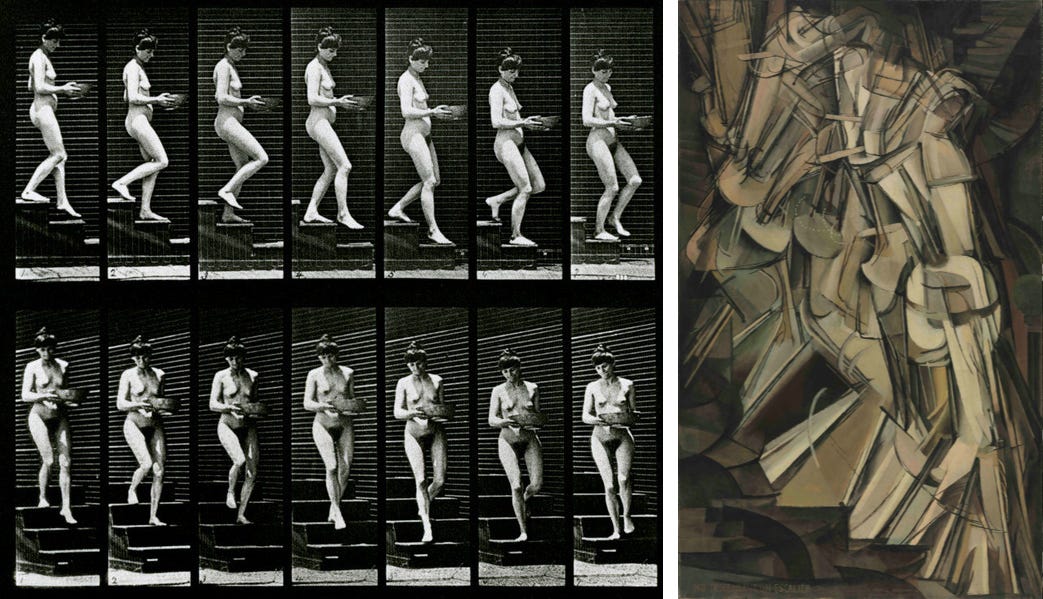

But this is not, historically, the kind of process that leads to great art. Great artists question the standard tools, materials, and styles. When the Industrial Age introduced manufactured paint, pre-stretched canvases, and other conveniences, for example, many artists adopted the new, factory-made materials and continued working in their old style. But the artists we remember didn’t. They took the commoditization of art as their subject. Thus we have Duchamp’s readymades (the urinal and the bicycle wheel, among others) and his Nude Descending a Staircase, which depicted the nude as recorded by rapid camera exposures, a technique that captured people and animals in motion, as well as much public attention. In both painting and sculpture, Duchamp showed how mass production was changing the way we perceived and thought about the world.

Similarly, Picasso and other cubists made work that subverted the classical techniques of representation in painting: the conversion of 3-D space to 2-D, of light to paint, of continuous movement to frozen scene, and other perceptual tricks used for centuries to render things "realistically."

The qualities that make Duchamp’s and Picasso’s work so funny and worthwhile are not qualities that AI extracts from its training data. Picasso didn’t merely "learn" the textures, shapes, or color palettes of classical painters, he contradicted and parodied them. Duchamp didn’t put a urinal on a pedestal because he was "trained on" the art of his predecessors. He subverted the whole concept of art in order to say something new about the present.

Can generative AI be used to say something new about the present? Yes, but not if the generated output is used in a finished piece (or as a finished piece). Consider the work of Heather Dewey-Hagborg, who began experimenting with algorithms more than twenty years ago. She initially wanted to use AI to simulate human behavior, but "the more I learned about the technology and its social context," she wrote in 2011, "the more interested I became in subverting it." In a piece called How do you see me? (2019) she took a facial recognition system, the kind that increasingly surrounds us in public places, and had another AI system "learn" how to deceive it. The latter created images that were "recognized" as her face but which look nothing like her, or any human face. This was possible because AI systems model the world in strange, pixel-based ways that are nothing like human perception. Her work shows that when we anthropomorphize computers we misunderstand what they’re doing. The idea that an algorithm can "recognize" images or speech, she concluded, is "hilariously erroneous." Unfortunately, in the years since she wrote those words, naïve trust in facial recognition systems has led to the arrest and incarceration of innocent people.

One problem with machine learning is that machines learn in the dumbest, most rote kind of way. It can’t make the jump from specific cases to abstract concepts. Or it can, but, as Dewey-Hagborg shows, not well. It learns something about faces, but something very different from what humans learn. In certain applications, this is AI’s great asset. When a learning algorithm is used to predict the weather, for example, it analyzes thousands of variables, more than any human could make sense of. These variables don’t need to be fit into coherent categories. They just need to be a reliable record of the past, from which AI extrapolates the future. "More like this" is what learning algorithms give us. More weather like the weather of the past. Or, in the case of generative AI, more images and text like the ones we’ve already seen and read.

When predicting natural phenomena, like weather or protein folding, staying close to what’s happened in the past is a good idea. The physical world behaves in 2024 much like it did when an apple fell on Isaac Newton in the 1600s. But human situations are constantly evolving. "More like this" is not a good model for artistic and cultural progress. As the dominant mode of creativity, AI would stop our culture in its tracks.

A few years ago, this whole discussion would have been an academic. Today, it’s at the center of a legal battle that could permanently alter what kind of art our culture supports. Since January 2023, authors and artists have filed more than a dozen lawsuits arguing that AI companies are committing copyright infringement by using their work for training. To which tech companies (and Louis Menand) have responded that if it's fair use for humans to learn from books and art, then it’s fair for AI to “learn” from them too.

Judges might not agree. The purpose of copyright is to foster a culture that makes great creative work. The law does this by providing a financial incentive for spending years of hard work on risky but potentially important art. AI might help the average person churn out emails or generate imitative art, but if it discourages high-level, culture-advancing creativity, then it's not aligned with the purpose of copyright. Already, some writers have stopped publishing online, and at least one author has halted publication of her e-book, by a major academic press, so its text wouldn’t be scraped for AI training. In its current, aggressive form, AI funnels revenue formerly earned by creative people straight to publishers and tech companies. It could create a situation in which earning a living through creative work is no longer possible. The fair use doctrine exists to prevent copyright-holders from inhibiting the creativity of others, but it can’t do this by reducing the incentives that are copyright’s main remit.

Does the quality of AI’s output matter? Louis Menand argues that it doesn’t. "If [ChatGPT’s poems] are banal, so are most poems," he writes. "God knows mine are." Perhaps that’s true, but Menand has never claimed to be a poet. Instead, he’s a writer of extraordinarily good prose. In his books, he takes an immersive, biographical approach to history, describing what he calls "vertical cross-sections" of culture. His writing is instantly recognizable and always insightful. (I’m a huge fan, and it gives me no joy to be criticizing the one disappointing piece he’s written.)

Menand argues that "every type of cultural product is a public good," which is a nice, democratic attitude. But AI-generated home repair websites with misleading diagrams are not a public good. Neither are AI-generated travel websites with bad info about foreign countries. We recognize garbage when we see it in our streets and waterways; we need to recognize it in the digital space too. Otherwise it may bury everything that matters.

It’s already starting to. Amazon.com is selling thousands of junky AI-generated books. Many of them use real authors’ names, intending to confuse potential readers and steal revenue from writers. AI-generated books are also being indexed by Google Books, indicating Google’s intention to legitimize them. And a sci-fi magazine had to shut down submissions last year after being overwhelmed by AI-generated stories. We’re still in the early days of AI, and the technology is being used to shut down opportunities for human authors and artists, and making it harder to find good work.

Those who argue that AI training is fair use are proposing a strange situation: humans, who are the only real source of knowledge and creativity, need to pay for books and art, while corporations building products that could start an avalanche of second-rate derivative work can have access for free. What kind of culture would these incentives lead to?

The constant, inaccurate comparisons between AI to humans only confuse the issue. In defense of AI, Menand asks, if "I don’t need permission to read…poems. Why should ChatGPT?" The question is nonsensical. You might as well ask whether a car needs a license to travel the roads, or whether a gun needs permission to shoot bullets. A lot of smart people are deeply confused about what’s going on with AI, and the tech industry has been quick to exploit it.

It is, of course, OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, Anthropic, and other powerful corporations that are taking books and art to build generative systems, passing them off as "creative," and profiting from the results. Shifting responsibility from company to product is part of the shell game of "artificial intelligence." Like in any good shell game, the prize isn’t where the hustler points. The future of our culture may depend on whether we get better at recognizing the illusion.

Brilliant critique, Alex. Thank you.